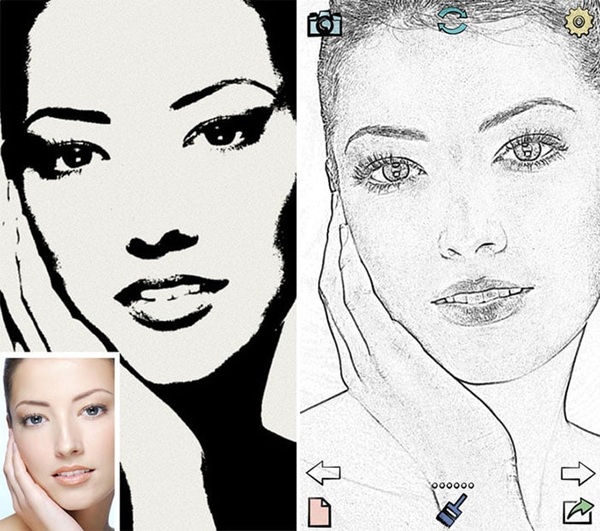

Turning a digital photograph into an image into line drawing depends critically on photo quality. Clear, high-resolution photos with lots of details provide algorithms enough of information to find textures and edges. Low-resolution or grainy images, however, may result in sketchy sketches that just highlight the fundamental ideas. Every picture tells a tale that directs the conversion process. Every pixel’s clarity can either make or ruin the final sketch.

The process starts with an analysis of the clarity of the image. Crisp details enable computers to more precisely identify lines and forms. Sharp photos allow the conversion program to create gentle gradients and seamless shapes. Still another important consideration is contrast. High contrast images highlight subject outlines, so the conversion tool can readily identify the differences between shadows and light. Every picture basically tells the conversion program, almost as though it were speaking with the computer. The language of light and dark says volumes about the form of the subject.

Early technology in line drawing conversion was shockingly straightforward. Using fundamental mathematical formulas and threshold settings, algorithms would find edges. Pixel-by- pixel comparison dominated the technique. Back then, the conversion was sometimes strict and gave little space for artistic liberty. Digital painters and photographers have to operate with photographs taken under ideal lighting conditions. It was a time when too much noise or grit might totally throw off the change. The conversion method was mechanical and offered artists extremely little influence over the outcome, regardless of photo quality.

Variance in capturing events and photo quality provide various difficulties. Little exposure problems can cause the final drawing to lose detail. One could remember days when significant processing durations and several passes over the data were part of the conversion image process. Past procedures were slow and predictable unlike the dynamic and participatory approaches of today. Once depending on an outside creative process, film photographers discovered their limitations in available technology. The path from pixel to line called for exploration and patience.

Smart approaches started to be included into advanced algorithms. Computers began to forecast which parts of a picture matter most when machine learning entered the scene. Programs learnt via instances instead of just applying set mathematical guidelines. These instruments developed their sensitivity to fine edges and delicate details throughout time. Imagine a painter who develops his ability with every brushstroke after learning his trade via many drawings. The conversion technology of today combines statistical analysis with innovative ideas derived from enormous archives of images. For graphic designers and artists, this method has provided fresh opportunities.

How crisp or dynamic a converted drawing looks still depends on photo quality. For example, high-quality photos provide smoother lines; lower-quality snaps could cause too strong strokes. Sometimes the flaws define the artistic worth. Sometimes a blurry picture makes one homesick for old pencil sketches. To provide personality, artists have also dabbled in combining hand-drawn methods with computers. While some purists follow exacting standards, others discover that embracing imperfections gives their work surprising appeal.

One finds intriguing how technology has changed throughout the years. Early days saw programmers and scientists working with little processing capability. The change needed heavy-duty computations, hence real-time processing was only a fantasy. Designers made their adjustments by hand and by walking through every frame. Often the finished result was somewhat stiff. Better computing techniques over time let for more flexible adaptations. Powerful hardware drives today’s systems to handle even the toughest low-resolution images in seconds. These developments have made experts and enthusiasts equally able to enjoy the art of conversion.

Modern programs give a wide spectrum of personalizing choices. To vary the degree of detail shown, artists can use several filters or change settings. A well-lit studio shot might be turned into a soft, elegant outline; a gloomy image might develop into a bold, strong sketch. Some programs even replicate the texture of the pencil, therefore capturing the roughness of hand-drawn lines. These choices let consumers not be prisoners to the original picture quality. Rather, students have several artistic options to negotiate the conversion process and create personally felt works of art.

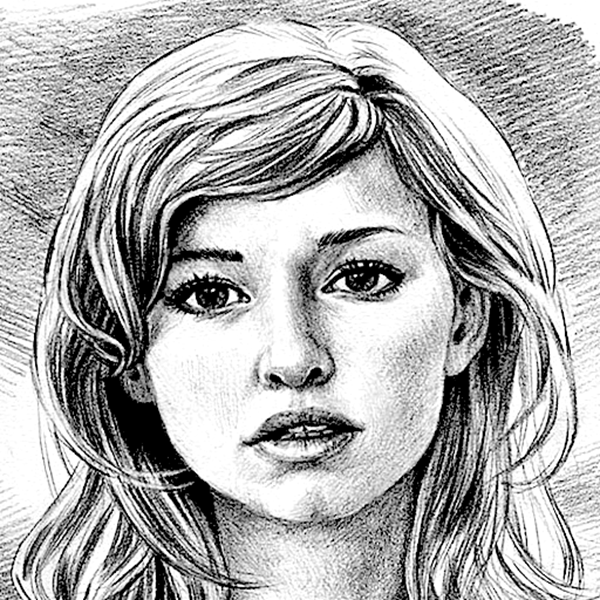

Stories from graphic artists help to clarify the changes in conversion procedures. One seasoned illustrator described early software versions as like using a ruler and compass without a clear direction. Every line created seemed very stiff, and little subtlety was caught. The program can today detect a minor change in a shadow or a delicate gradient in the light. For artists, this evolution has created far more possibilities and made the change as natural as turning spoken words into an illustrated narrative. Nowadays, the technology speaks to human creativity so the artist may choose how the machine understands reality.

Developments in artificial intelligence have improved the conversion process yet further. Algorithms today change with the content of the picture. They consider textures that distinguish fabric, hair, or even the bark of a tree. Such advancements make it easier to capture organic structures. The strategy utilized by software has strayed from hard-coded formulas to learning-based models that are curious about specifics. For individuals who love experimenting, this shift is like possessing a magic wand. You can customize casting spells that change the mood and tone of your sketch.

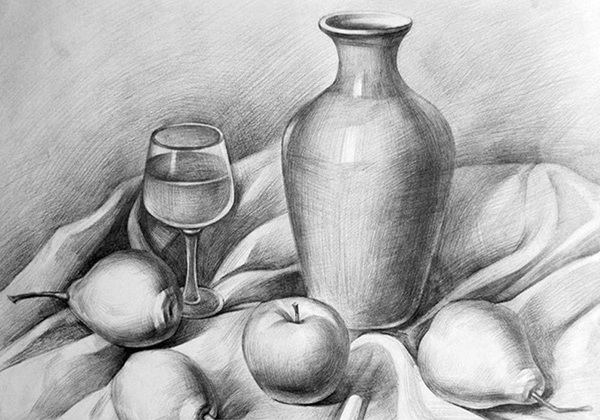

Photo conversion also shocks with changes from one moment to the next. One occasionally finds delicate line drawings arising from images with soft illumination and subdued curves. Sometimes a picture taken during golden hour turns into a sketch with striking shadows and rich contrasts. Every method opens different creative opportunities. A portrait under soft light, for instance, can turn into a beautiful piece of art inspiring silent reflection. On the other hand, a high-contrast night view may generate a drawing bursting with dynamic energy.

Photo quality affects conversion in ways other than only clarity and brightness. Colors also surprisingly have a part. Though line drawings are usually monochrome, the underlying color channels can influence the finished work. Before stripping off the colors, some conversion programs examine color contrasts. This stage can expose minute elements enhancing a created sketch. Every color helps to create the hierarchy of lines in turning color photos into line art. The process becomes a negotiation between what remains in the image and the abstract representation the software develops.